- Olga Dudchenko

- Sep 12, 2019

- 2 min read

The canyon mouse (Peromyscus crinitus) is native to North America [1]. Its preferred habitat is arid, rocky desert making it a great model organism to study adaptation to desert. Gaining a deeper understanding of desert adaptation (e.g., osmoregulation and water metabolism) is important for conservation, climate change studies, and human health (for instance, understanding kidney disease).

In collaboration with the MacManes lab at the University of New Hampshire, today we share the chromosome-length genome assembly for the canyon mouse. The draft genome assembly was generated using 10X data by Matthew MacManes, Anna Tigano and Jocelyn Colella at the University of New Hampshire. The fibroblast culture for Hi-C library preparation came from the archive collected at the Texas Medical Center.

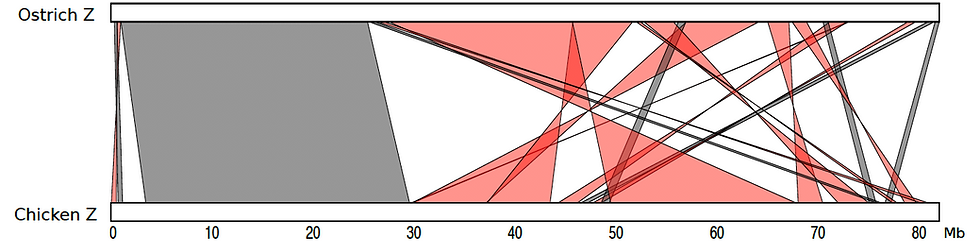

Check out below how the new genome assembly compares to a publicly available genome of a close relative, the prairie deer mouse (P. maniculatus, ~5MY divergence [2]). The genome assembly, HU_Pman_2.1, was shared by J.-M. Lassance and H.E. Hoekstra at Harvard University and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, here. We also include a comparison to the golden hamster chromosome-length genome assembly (Mesocricetus auratus, upgrade of genome assembly MesAur1.0), a rodent from the same family from the DNA Zoo collection (Cricetidae, ~20MY divergence [3]).

It is worth noting that the sample used for Hi-C library preparation proved to have a polymorphic karyotype. The fasta shared today represents one of these karyotypes, the one most consistent with an individual animal used to create the draft genome assembly. We are now working to sequence more canyon mice to figure out if this polymorphism is a feature or a bug. So, stay tuned for more info on this, and for more Peromyscus genomes and data!