- Olga Dudchenko

- Aug 29, 2019

- 2 min read

The common ostrich Struthio camelus is the largest living bird: a male ostrich can reach a height of 9.2 feet (2.8 meters) and weigh over 344 pounds (156 kilos) [1]. Ostriches are flightless. In the 18th century, ostrich feathers were so popular in ladies’ fashion that they disappeared from all of North Africa. If not for ostrich farming, which began in 1838, then the world’s largest bird would probably be extinct [2]!

Today, we share a chromosome-length genome assembly for the common ostrich. This is an upgrade from a draft generated by the Avian Genome Consortium, see (Zhang, Li et al., Science, 2014) and accompanying papers for more details. We thank the Oklahoma City Zoo for providing us with a sample used for Hi-C library preparation!

Birds are divided into two clades, the paleognaths and the neognaths. The paleognaths are a much smaller clade, and with the exception of the tinamou, they are flightless. With today’s upgrade to ostrich, we’ve now released chromosome-length assemblies of most of the paleognath genera (the ostrich, the emu, the cassowary and greater rhea). To complete the collection, we’re still looking for samples of tinamou and kiwi - if you have a sample, even a pretty low-quality sample, it could make a big difference. Please consider sending it along!

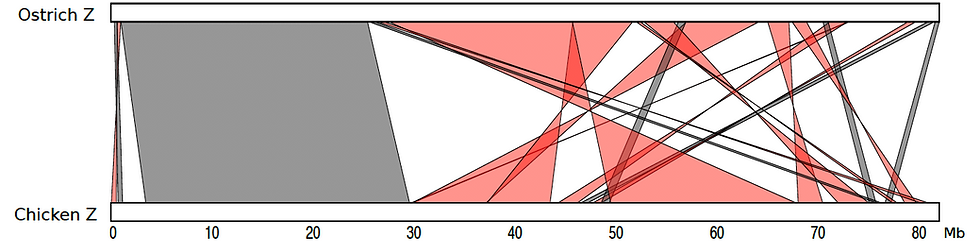

Below is a whole-genome alignment plot comparing the ostrich chromosomes to those of the other paleognaths in our collection: the emu, the cassowary and greater rhea (all DNA Zoo upgrades from Sackton et al., Science, 2019). Also included is the alignment to the chicken chromosomes, from the International Chicken Genome Sequencing Consortium.

Because the original draft and the Hi-C signal have been generated using samples from female birds, both Z and W chromosomes are represented in the DNA Zoo assembly. The structure of the ostrich Z was recently explored in (Yazdi and Ellegren, Genome Biol Evol, 2018). There, they generated a genetic map for the ostrich Z chromosome (chr# 6 in the new genome assembly), building on 2015 improvements using optical mapping data from (Zhang et al., GigaScience, 2015).

It is worth noting that while we have not used the optical and genetic mapping data for our assembly, our conclusions on the syntenic relationship between the ostrich Z and the chicken Z, shown above, broadly agree with those suggested by the published genetic map (see figure below). These suggest a large ~30Mb collinear region near the p-end of the sex chromosome. The highly rearranged portion towards the q-end (~50Mb) corresponds to the pseudoautosomal region (where recombination is possible between the Z and the W chromosomes).